Grace Presbyterian Church

September 4, 2016, Pentecost 16C

Philemon

Doing What’s Right No Matter What’s Wrong

You can now go and

complain to your friends who attend other churches that you have an extremely

long-winded preacher, and you can tell them that he read an entire book of the

Bible during the service as proof of that fact.

In all

seriousness, though, this slender letter should not be overlooked, as the book

has had an influence seemingly out of proportion to its size across the history

of both the church universal and the church particular in this country, and

even more particular in this part of this country. That influence was not good,

largely because those who interpreted it did so more for their own convenience

than for any genuine desire to learn from it.

You see, this

little letter became, in such empires or nations as sanctioned the practice, a

primary scriptural justification for the institution of slavery. That list of

such nations, of course, includes the United States for about the first two

hundred years of its colonial and national history. To be blunt, back then the

only reason you’d have ever heard a sermon on Philemon was in order to support

or prop up slavery as “biblical,” frequently (although not exclusively) in the

southern part of the country, in churches that separated from their northern

fellow churches over slavery – including, yes, Presbyterians.

The tragedy of it

is that this could only be done by emphasizing something that is not in the

letter. For all that Paul says in the letter, there is one thing he does not

say: “Slavery is wrong.” Neither does

he explicitly order Philemon to free the slave Onesimus (although in verse 8

Paul does claim the spiritual authority to do so). And hey, if Paul doesn’t say

slavery is wrong, then it must be OK, right?

To be sure this

was not the only such passage of scripture that preachers of the past would

have used to justify slavery, but it was damaging nonetheless all out of

proportion to its size, and completely contrary to the spirit of the burden

that Paul laid upon his “dear friend and

coworker” Philemon.

Now I could have

left off some of the preliminary and concluding verses of this chapter in the

interest of shortening the reading and focusing on the “important stuff” in

this little letter. In the case of this letter, though, the preliminary and

concluding verses of the chapter are really part of the “important stuff.” The

salutation of this letter names other members of the “church that meets in your house,” specifically “Apphia our sister” and “Archippus our fellow soldier”. This

wasn’t a real ‘private’ letter; the whole community is being invoked and

included here, and what Paul asks of Philemon is in effect being asked of the

entire community, not just the one who actually owns the slave in question.

Ah, that brings us

to the central character, or object, of the letter. Onesimus was a slave, this

much is clear. Even if there were no other clues about his identity his name

itself would be a giveaway; the name ‘Onesimus,’ which translates as ‘useful,’

was not a name given to a free-born person in the Roman Empire. Would you name

your child ‘Useful’? (And yes, this does give a little extra weight to Paul’s

words in v. 10 about Onesimus being formerly “useless” but now “useful”.)

Onesimus’s

situation is a little less clear. Most interpreters of this letter seem to

believe that Onesimus had run away from his master. Others suggest that possibly

Onesimus was guilty of some other wrong against Philemon, possibly involving

some kind of theft, or that he had made some mistake that had cost Philemon in

some way. Whatever the reason, there is some reason for Onesimus to fear

returning to Philemon and Paul is interceding on his behalf, via letter (he

can’t do so in person because he’s in prison, remember).

As is often the

case when you only hear one half of a conversation, there’s a lot about which

we can’t be sure. But one thing is inescapable; how Paul envisions Onesimus

being received by Philemon (and Apphia, Archippus, and the church in his house)

is dramatically different than the way Onesimus had functioned in Philemon’s

household before. Dramatically, life-alteringly different. Possibly-threaten-your-place-in-Rome

different. Paul gets that Philemon has to choose, himself, to take this radical

step.

Don’t let’s kid

ourselves; Paul is not asking Philemon to readmit Onesimus to his former slave

status, not calling for a return to status quo. A reset, a return to status quo

would not require requests like these:

·

Paul calling Onesimus “my child” “whose father I

have become during my imprisonment” (v. 10);

·

Paul telling Philemon “I am sending him, my own heart, back to you” (v. 11);

·

Paul saying that Philemon could receive Onesimus

back “no longer as a slave but more than

a slave, a beloved brother … both in the flesh and in the Lord” (v. 16);

·

Paul charging Philemon to “welcome him as you would welcome me” (v. 17).

This isn’t “take

him back and I’ll make up your loss and nothing changes,” not by a long shot.

This is “change everything.” This is “totally turn things upside down.” And it

certainly is not how any self-respecting Roman citizen treats a slave. If you

can figure out how to treat a piece of property with no legal or cultural or

even human status as a “beloved brother”

or sister, the way you would treat the man who brought the gospel of Jesus

Christ to you, well, you’re evidently cleverer than me.

What Paul asks is

not without consequence for Philemon; you didn’t just free your slaves all

willy-nilly and get away with it. Besides the social stigma and cultural

backlash such an act likely to face, Philemon could face even legal

consequences for such treatment of Onesimus, even if he did not technically “free” Onesimus. Anything that had

even the potential of setting off unrest among slaves or upsetting the social

order could be clamped down by the heavy hand of Roman authority; and seeing

Onesimus gaining status and acceptance in Philemon’s household beyond their own

could very well upset the order of society in his community. Paul does not

care, evidently, and engages in monumental arm-twisting to persuade Philemon to

take this step, while in every technical respect leaving the choice in Philemon’s

hands (albeit, as noted earlier, placed in the context of the community of

faith in which Philemon lived and moved; Apphia and Archippus and the church.).

While I doubt

there are too many today who would seek to restore the discredited practice of

using this letter to justify slavery, there are plenty of forms of oppression

that fall under the ban if we take this letter seriously. Racism simply cannot

stand in the face of a call to love others as beloved sisters or brothers. Any

kind of bigotry at all, any claim that the world would be just fine if they would just “stay in their place” or

“not rock the boat” or simply stay quiet and out of the way, has no place in

the mind of a follower of Christ, no matter how entrenched or enmeshed in our

culture such an attitude may be. “That’s

just the way it is” might have made a great song for Bruce Hornsby back in

the 80s or 90s or whenever, but it can never be the

response of a follower of Christ in the face of any injustice or oppression. (And if you remember the song, even

Hornsby wraps that chorus with the imperative “but don’t you believe it”. Neither should we believe or accept it.)

If it is a

coincidence that this scripture happened to fall on a Sunday when the Lord’s

Supper is being observed, it is a happy one indeed. The table of the Lord is

decidedly non-selective about who is welcomed. Anyone – anyone – who calls upon the name of the Lord is welcomed as beloved

brother or sister. In those great miraculous feedings out in the countryside,

Jesus didn’t send his disciples to weed out the undesirables from the crowd;

all were fed. And if that fact produces anything other than an “amen” from us,

it might be well for us to remember that this openness might just be to our

benefit.

We don’t actually

know what Philemon did in response to Paul’s letter. There are some hints that

his response was somehow affirmative; after all, it seems unlikely that such a

personal and particular letter would have come into the canon of scripture,

even under the Holy Spirit, if Philemon had responded to Onesimus’s return with

thirty lashes and an order to “get back

to work, Useless.” Also, we know that later in the century, there was a

bishop in the church, seated in the city of Ephesus to succeed Timothy, with

the name Onesimus. Even if it isn’t the same Onesimus, it does suggest that somebody’s slave became a “beloved

brother” along the way. In my head, to be sure, I want to see Philemon and Onesimus

(and Archippus and Apphia and the whole church in their house) side by side

coming to the table to receive the bread and cup. But we don’t know, not for

sure.

But in a way, not

knowing the outcome places the burden of answer on us. How do we respond to

that one who, like Onesimus, has never been of any status or place or even

humanity to us, but who is now set before us with God’s command to love him or

her as a beloved brother or sister, one of God’s own children, no matter how

vexing it might be to us?

For the call to

answer that question, Thanks be to God.

Amen.

Hymns: (from Glory to

God: The Presbyterian Hymnal)

#744 Arise,

Your Light Is Come!

#457 How

Happy Are the Saints of God

#754 Help

Us Accept Each Other

#695 Change

My Heart, O God

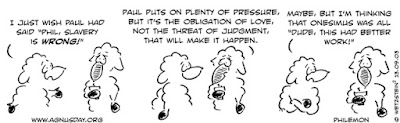

Credit: agnusday.org. Everybody wishes that, but that's not the way it is...

No comments:

Post a Comment